For centuries, Japanese stone gardens, karesansui, have been an object of fascination, holding both an

aesthetic appeal and psychological allure. Japanese stone gardens are designed

with zen principles

and purposes dating back to the 11th century.

The history behind stone gardens

helps elucidate their intrinsic qualities. Analysis of the gardens elements

helps to identify how the viewer receives such an intense emotional effect.

Primary examples of stone gardens include the Ginkakuji in Kyoto and various

gardens within the Daitokuji complex.

The history behind stone gardens

helps elucidate their intrinsic qualities. Analysis of the gardens elements

helps to identify how the viewer receives such an intense emotional effect.

Primary examples of stone gardens include the Ginkakuji in Kyoto and various

gardens within the Daitokuji complex.

Definition

Japanese stone gardens are small, walled, stylized

landscape containing carefully arranged rocks, moss, raked gravel and sand and

pruned trees and bushes. They are viewed outside of the landscape, often

the porch of the hojo, the dwelling of the chief monk of

the temple or monastery. Zen gardens are intended to imitate the essence of nature;

for instance, raking sand into swirls is a representation of water ripples.

History

“Classical”

zen gardens were created during the Muromachi Period, beginning in Kyoto, Japan as a product as Zen Buddhism. They

were used to facilitate meditation about the true meaning of life. Speculation

dubs this the reason why the ‘essence’ of nature is captured in stone gardens

rather than nature itself, reducing all its forms into rock and significantly

simplifying its intricacies; so that it may be more clearly understood.

Dry

landscapes kare-sansui, decreed the

Sakuteiki, have “rocks placed upright like mountains, or laid out in a

miniature landscape of hills and ravines, with few plants…[occasionally in the

style of] a stream or pond, including the great river style, the mountain river

style, and the marsh style. The ocean style features rocks that appeared to have been eroded by

waves, surrounded by a bank of white sand, like a beach.” This excerpt exemplifies

how stone gardens attempt to replicate nature. The main elements of white sand

and gravel have long been a feature of Japanese gardens, symbolizing purity in

Shinto religion and water, or like white space in Japanese paintings, emptiness

and distance in zen gardens.

The

classic zen gardens arose in the Muromachi Period (1336-1573), simultaneous with

the Renaissance in Europe. Though the Muromachi Period contained various wars

and political disorder, it also began the Noh theater, Japanese ceremony, shoin style of

Japanese architecture and most importantly Zen Buddhism. Samurai class and war lords

admired the self-discipline doctrine. Early zen temples followed Chinese

gardens with lakes and islands, but were modified by the 14th and 15th

century to completely stimulate meditation. This primarily took place in Kyoto,

the hub of new culture.

“Nature, if you made it expressive by reducing it to its

abstract forms, could transmit the most profound thoughts by its simple

presence. The compositions of stone, already common China, became in Japan,

veritable petrified landscapes, which seemed suspended in time, as in a certain

moments of Noh theater, which dates to the same period."- Michel Baridon

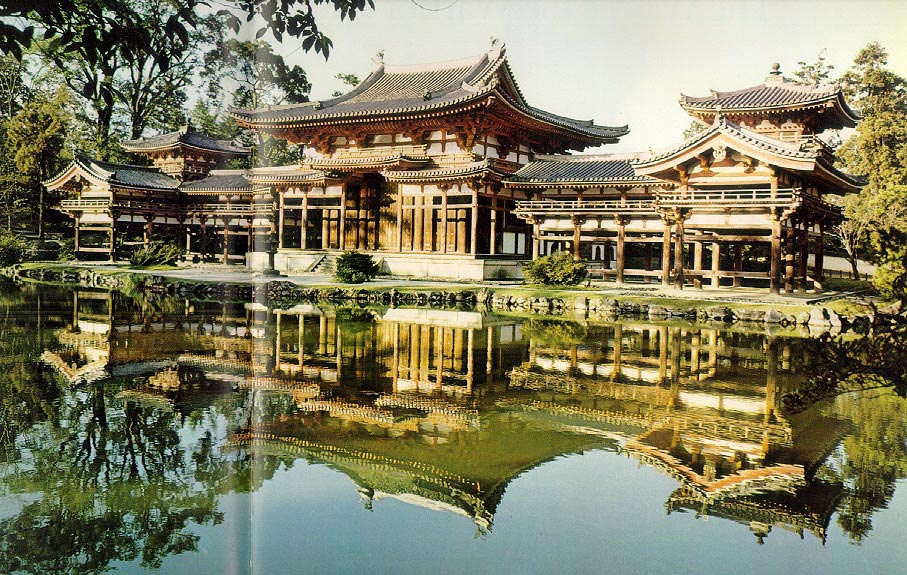

Saihō-ji, "The Temple of the

Perfumes of the West," (Koke-dera, the Moss Garden) is thought to

be the first garden to transition to the new style. It was formed by Buddhist monk Musō Kokushi, who modified a Buddhist

temple into a zen monastery in 1334.

Upon examination, the lower garden is

in the traditional Heian

Period style. This consists of the ground representing a pond, with several

rocks representing islands. The upper garden is a dry rock garden which

features three rock "islands”:

-Kameshima

is the island of the turtle, and resembles a turtle swimming in a

"lake" of moss.

-Zazen-seki

is a flat "meditation rock." Meditation rocks are thought to transmit

calm and silence.

-Kare-taki,

is a dry "waterfall" composed of a stairway of flat granite rocks. Interestingly,

the most famous attribute of the moss is only a recent development and has now

grown to symbolize water.

The second classic example to follow was Kokushi’s next achievement in Tenryū-ji, the "Temple of the Celestial Dragon". It was strongly influenced by Song Dynasty paintings where mountains rise in the mist, reminiscent of depth and height. Again it is evident that nature is depicted as abstract and stylized. Muso Kokushi went on to build gardens of Ginkaku-ji, also known as the Silver Pavilion, which are noted for the innovative new pile of gravel, representing Mount Fuji. This design is now known as kogetsudai, or “small mountain facing the moon.” It has prompted other similar techniques that are called ginshanada, literally "sand of silver and open sea" as the landscape for which Mount Fuji is set.

Ryōan-ji, is said to be

the first purely abstract garden, constructed in Kyoto in the late 15th

century. No certainty of its representation is reached, although recently Gert

van Tonder of Kyoto University and Michael Lyons of Ritsumeikan University

suggest the rocks form the subliminal image of a tree. Researchers claim that

the mind can note the relationship between the rocks, creating the calming

effect. In comparison, Daisen-in

can be quite literarily analyzed; “a river of white gravel represents a

metaphorical journey through life; beginning with a dry waterfall in the

mountains, passing through rapids and rocks, and ending in a tranquil sea of

white gravel, with two gravel mountains.” In other words, the river of life.

Design

As rocks are the main element,

their selection and placement is crucial in creating the design of the garden.

The phrase for “creating a garden” is actually synonymous for “setting stones” : ishi wo tateru koto; literally, the "act

of setting stones upright.” If the rocks are placed incorrectly, the owner of

the garden would suffer misfortune.

Stones are classified as tall vertical, low vertical, arching,

reclining, or flat.

Tall vertical - Stones taller than it is wide; used on the taller half of a waterfall or as the central stone in a composition.

Low vertical- Stone is wider than it is tall; used to complement tall vertical stones

Arching - Oddly shaped stone overhangs on right or left; used to "give strength and stability to vital points of the garden such as the corner of a stone bridge. To achieve this a stone can be planted at an angle to make a moderate arch more prominent."

Reclining - Stone in shape of a reclining animal "with the head on one end higher and narrower than the hips on the opposite end. Masters use this diagonal top line to draw the eye to another element close by in the garden, almost as though it is a pointer."

Flat - Stones less than a foot tall, but it may be very long and wide with a flat top surface; used in front of a composition , at water's edge, and as a bridge.

Different natural elements are

represented in various ways. For instance, "mountains” are symbolized by igneous volcanic rocks,

or sharp, jagged mountain rocks. “Seashore” or river borders for gravel sea are

created using smooth,

rounded sedimentary rock. Rocks with animal-like or other strange features were not

prioritized as they are in Chinese gardens. Emphasis is placed less on

individual rocks and more on the ‘harmony of composition.’

The harmony of composition was

created intricately and strategically. Some of the principle rules outlined in

SuXX read as follows:

"Make sure that all the

stones, right down to the front of the arrangement, are placed with their best

sides showing. If a stone has an ugly-looking top you should place it so as to

give prominence to its side. Even if this means it has to lean at a

considerable angle, no one will notice.

“There should always be more

horizontal than vertical stones. If there are "running away" stones

there must be "chasing" stones. If there are "leaning"

stones, there must be "supporting" stones."

“Rocks should be rarely if ever

placed in straight lines or in symmetrical patterns.”

“The best arrangement is one or

more groups of three rocks.”

These reasoning behind these rules

are not purely for aesthetic pleasure, but again are meant to be symbolic. A

popular triad arrangement has one centric tall vertical rock surrounded by two

smaller rocks, and is represent Buddha and his two attendants.

Other common combinations include:

-A tall vertical rock with a reclining rock

-A short vertical rock and a flat rock

-A triad of a tall vertical rock, a reclining rock and a

flat rock

Important factors also include variation in color, shape and

size of rock. Bright colors are avoided so as to not distract the viewer, and

grains ought to run in the same direction to promote unity and fluidity. The

number of vertical and horizontal rocks should be balanced.

Sauteishi, "discarded"

or "nameless" rocks were used towards the end of the Endo period, placed

in seemingly random places to ‘add spontaneity’ to the garden.

The second element in addition to

large stones is gravel. Gravel is preferred over sand because it is less

disturbed by rain and wind. Gravel is not only used as theswirling, sea background

upon which the large stones are placed. The physical act of raking the gravel into

ripples and waves helps Zen priests concentrate. The lines must be perfect. The

pattern often unfolds after the stones are placed, reliant upon their placement.

Not all patterns are rigid, creativity is considered a challenge.

Symbolism

Stones function to represent all

landscapes, from mountains to water. Stones and manicured shrubs, karikomi,

hako-zukuri are used interchangeably. Moss is functions as "land"

covered by forest. The mountains are often in imitation of Horai, the legendary home of the Eight Immortals in Buddhist

mythology. Large stones can also be boats, or creatures- particularly turtles

and carps. As a group they may symbolize a waterfall, or a flying crane.

Some speculate that the gardens also held a political message in the Heian period. Sakutei-ki wrote:

"Sometimes, when mountains are

weak, they are without fail destroyed by water. It is, in other words, as if

subjects had attacked their emperor. A mountain is weak if it does not have

stones for support. An emperor is weak if he does not have counselors. That is

why it is said that it is because of stones that a mountain is sure, and thanks

to his subjects that an emperor is secure. It is for this reason that, when you

construct a landscape, you must at all cost place rocks around the

mountain."

But some gardens have no concrete

definition to their composition. In contrast, garden historian Gunter Nitschke

wrote about gardens: "The garden at Ryōan-ji does not symbolize anything,

or more precisely, to avoid any misunderstanding, the garden of Ryōan-ji does

not symbolize, nor does it have the value of reproducing a natural beauty that

one can find in the real or mythical world. I consider it to be an abstract

composition of "natural" objects in space, a composition whose

function is to incite meditation." This relates back to the original focus

of the Japanese stone gardens: to elicit peace, and provoke thought, rather

than just relay an image.

Other Zen garden influences

The invention of the zen garden was

concurrent and connected to developments in Japanese ink landscape paintings.

Japanese painters such as

Sesshū Tōyō (1420–1506) and Soami (died 1525) simplified their works of

nature, including only its most basic aspects and leaving the background blank.

More evidence is accrued when it is noted that Soami supposedly help design both

Ryōan-ji and Daisen-in, though this was never documented.

Karesansui garden scenery is known to be inspired originally from Chinese and later also Japanese, landscape paintings. Like paintings, the gardens depict natural landscapes; they also use simplicity to evoke calm instead of overwhelming the viewer with detail. Some gardens are thought to be direct translations of a specific scene. The technique of “borrowed scenery”, such as hills in the background, is also sometimes incorporated; Shakkei. Ink painting is still retained in Buddhist work; and Japanese stone gardens are considered art.

Allure

Buddhistic

principles circulate Mahayana Buddhism, circulating around meditation. The

garden is structured thus to elicit tranquility and guide the meditator to a

higher state of calmness. The stone’s placement is not solely based on the

natural image in mind, where rocks symbolize mountains and gravel the sea that

surrounds them.

Aesthetically, the larger stones

are the main object and the smaller stones used to guide the eye towards them,

raked in strategic curves leading to them or encircling them, focusing

the eye. The smaller stones are used to create a plane for the larger stone

centerpieces to sit, and are utilized to make soothing lines around them in a

clear path for the viewer to follow them. This process is soothing and results in

the simple design. Supposedly, their representation should additionally psychologically

stimulate calmness, that of mimicking nature. In this manner, both the view and

its meaning have principally calming effects. That their subject matter is and

of nature also deepens a more basic, purity of feeling and hopefully, of

thought.

Thus stone gardens are able to

elicit tranquility, through their appearance and their significance. In viewing

a stone garden from a distance, the viewer is also not submerged and must

reflect, and puzzle over the design. It is also therefore able to be viewed in

its entirety, as a whole rather than as glance by glance screen shots if you

were standing within it. As your eye travels, following the guided pattern, the

swirls reminiscent of sea and the natural asymmetry of piled stones, mountains,

within it- your mind may dolefully wander, and in observing the natural world

you may glean something from it.

There is certainly a purpose to the

garden, but even purposeless it has an effect. And even affectless, it has a

history. For these basic reasons alone people are consistently drawn to stone

gardens, their simplicity is captivating, their serenity remarkable and thus their

success is undeniable.

Today

Today, stone gardens have been

created and managed far from Japan on many different scales for many different

purposes. Gravel and large stones have been integrated into landscape design as

essential earth elements, and as essential partners as such. The basic

principles of the stone gardens can be maintained in much larger, complex

gardens; a corner of a

pond, a swirl of gravel to frame flowers rather than a pile of stones.

Moss is decorative in many instances, much less of a symbol- but always in collaboration

with stone. There is such a timelessness to the stone garden’s simplicity that

it can be assumed that stone gardens will persist, continuing to be an active

trend for gardeners and philosophers alike.

For more information, be sure to investigate the following sources

Young, David and Michiko, (2005), The Art of the Japanese Garden

Nitschke, Gunter, (1999) Le Jardin japonais - Angle droit et forme naturelle,

Baridon, Michel (1998). Les Jardins- Paysagistes, Jardiniers, Poetes

Murase, Miyeko, (1996), L'Art du Japon,

Elisseeff, Danielle, (2010), Jardins japonais

Klecka, Virginie, (2011), Concevoir, Amenager, Decorer Jardins Japonais

For more information, be sure to investigate the following sources

Young, David and Michiko, (2005), The Art of the Japanese Garden

Nitschke, Gunter, (1999) Le Jardin japonais - Angle droit et forme naturelle,

Baridon, Michel (1998). Les Jardins- Paysagistes, Jardiniers, Poetes

Murase, Miyeko, (1996), L'Art du Japon,

Elisseeff, Danielle, (2010), Jardins japonais

Klecka, Virginie, (2011), Concevoir, Amenager, Decorer Jardins Japonais